Main content

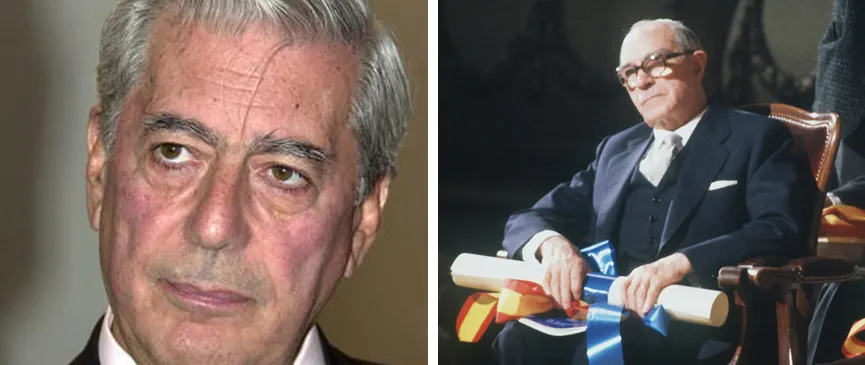

Mario Vargas Llosa and Rafael Lapesa Melgar Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 1986

Speech of Mario Vargas Llosa, Prince of Asturias Award Laureate for Letters.

I imagine that the task of expressing appreciation for the Prince of Asturias Awards has been entrusted to me because, of all the prize-winners, I can testify better than anyone to the noble spirit that is their inspiration and, as a visitor from distant Peru, to their world-wide interest. I discharge my duty with modesty but also with pride and sharing the recognition accorded me with the distinguished intellectuals, artists, scientists and institutions which merited these prizes. I am happy too to perform this task of appreciation in this land of Asturias, with its craggy peaks and green countryside, where Clarín, one of the writers I most admire, lived; this land of Asturias, a symbol in western History of devotion to sovereignty and liberty.

And since the Prince of Asturias Awards unite each year men and women of Spain and Latin America, this may be an opportune moment to reflect aloud on the watershed in History whose fifth centenary we shall soon celebrate: the inclusion of America in the western world through Spanish intervention. It is worthwhile to do this because, although ancient and well known, it is an event that isn't clear at all, nor do some governments and people draw from it the conclusions the facts demand.

We, Spaniards and Latin Americans have shared 300 years of common History and, in these three centuries, the continent Columbus discovered has disappeared and been replaced by another, substantially different. This is a continent which, though enriched with the contents of its pre-Spanish core and with what has come from other parts of the earth, mainly Africa, nevertheless thinks, believes, is organised, speaks and dreams within values and cultural parameters which are the same as Europe's. Whoever refuses to see this has an inadequate view of America and of the West's cultural horizon.

After three centuries when there was but one, the nations that Spain helped to form and on which she left an indelible mark broke up into a myriad of countries which, in the midst of fortune and misfortune - more the latter than the former - are trying to shape for themselves a becoming destiny and to wipe out those devils that have poisoned their History. Hunger, intolerance, evil, inequalities, backwardness, lack of liberty and violence, evils to which Spain is no stranger for they have damaged her too.

What History has united governments often take apart. Our past, in America, is marred by stupid quarrels, which have left us bloodstained and impoverished to no purpose. But all the wars and dissension haven't been able to penetrate deep; beneath the passing differences those links which Spain forged between herself and us, and among ourselves, and which time goes on strengthening remain unbreakable: a language, beliefs, institutions and a very wide gamut of virtues and defects which, for good or evil, make us relatives above our idiosyncrasies and differences.

Perhaps an anecdote could illustrate better what I would like to say. As I am a storyteller, let me recount it to you.

It's the story of a Peruvian indian born in 1629 or 1632 - nobody knows for sure - in a village lost in the Andes whose name, Calcauso, was not on any map. It was, probably still is, in the province of Aymaraes, in Apurimac. He was an inquisitive, bright lad. One day, a passing priest, impressed by his gifts, took him to El Cuzco and set him to study in the college of San Antonio Abad, where bursaries were granted to the sons of the poor. We know very little of his life. It isn't even sure that he was called by the Spanish name with which he has passed into History, Juan Espinoza Medrano. This much seems sure that he had a face pockmarked with warts, or an enormous mole to which he owed his nickname: El Lunarejo ('the spotty one').

But his contemporaries gave him another more illustrious name, the sublime doctor. For that indian from Apurimac became one of the most cultured and refined intellectuals of his time, a writer whose robust and trenchant prose, colourful, complex, with wide vision and daring images, founded in Latin America the baroque current whose tributaries, centuries later, would include writers like Leopoldo Marechal, Alejo Carpentier and Lezama Lima.

The legend says that when 'the sublime doctor' preached from the pulpit of the humble church in the San Cristobal district of El Cuzco where he was parish priest, the nave would overflow with faithful some of whom had journeyed far to hear him. Did that tightly packed throng understand what he said to them? To judge from his sermons, which have come down to, us - the collected edition is called exaggeratedly 'the Ninth Wonder of the World' - the majority didn't. But there is no doubt that his luxuriant, musical language which assembled authoritatively Greek poets, Roman philosophers, Byzantine story-tellers, medieval troubadours and the prose writers of Castille and made them all dance gaily through the imagination of his hearers charmed his audience.

The only book written by 'El lunarejo' that we know of is a polemical text: 'El apologético a favor de Don Luis de Góngora', which he published in 1662 to refute the Portuguese critic Manuel de Faria y Souza who had attacked the highly ornate, latinised style. There are people who will laugh at the intention of this stormy broadside. Wasn't it pathetic that so far from Madrid and so long after the original dispute, that indian undertook to join in a polemic which here in Europe had ceased several decades before and whose protagonists were already dead? The tardy role of the little priest from El Cuzco launching himself from his Andean fastness to the re-awakening of an extinct polemic moves me deeply. And why? Because in his erudite, aggressive text crammed with passion and metaphors there is the will to appropriate a culture, which anticipates intellectually, what is now the case in Latin America. In 'El Lunarejo' and in a handful of other indian creative writers, like el Inca Garcilaso of Sister Juana Inés de la Cruz, the ideas and language that passed from Europe to America have put down roots and a way of thinking and a aesthetic sprouted which already represented a different nuance, a very clear and characteristic tone within Spanish literature and western civilisation.

In 'El Apologético', 'El lunarejo' quotes and comments on more than 130 authors from Homer and Aristotle to Cervantes including el Aretino, Erasmus, Tertullian and Camoens. Learned quotations were a ritual of the times, like honouring heaven and the saints. In this case they were more, an exercise in sympathetic magic, a spell to attract to those lands and root in them the people who then represented the summits of wisdom and art. The witchcraft was effective: works such as those of Borges, Neruda and Octavio Paz have been possible in Latin America thanks to the stubbornness with which people like 'El Lunarejo' decided to make his and to assume as his own the culture which Spain planted in their land.

In the 'sublime doctor's' time, the greater part of our writers were mere copiers: they repeated, sometimes with real hatred, sometimes in a jarring way, the styles of the metropolis. But in some cases, as in this, a curious process of emancipation can be observed in which the freed man reaches his liberty and identity by choosing of his own free will that which formerly had been forced upon him. The colonised people takes possession of the colonial power's culture and, instead of just looking at it, goes on to create it by adding to it and renewing it. So integration is the measure of independence. In this lies the cultural sovereignty of Latin America, knowing that Cervantes, the Archpriest and Quevedo belong as much to us as to Asturias or Leon, that they represent us as legitimately as the stones of Machu Picchu or the Mayan pyramids.

That process was strange, tortuous, and above all, slow. Like the 'sublime doctor', other Latin Americans found their own voice, without deliberately indenting it, by trying to imitate the Spaniards. In 'El Lunarejo' inventive skill and verbal brilliance break the cramped and abject moulds of the genre he chose to express himself. His 'Apologética' is not really that, but a prose poem in which, on the pretext of venerating Góngora and vilifying Faria and Souza, the man from Apurimac unfurls a magical sleight of hand. He plays with sounds and the meaning of words, he fantasies, sings, implores, quotes, juggles and colours words with a feel all his own. At the end we don't see in his text a vindication of Góngora and a condemnation of the Portuguese: we see him emerge drunk with words and puns, with a shape so clearly defined that it reduces the poet and his critic to the level of shadowy ghosts.

In the 'Lunarejo' what Peru and Hispano-America would be is foreshadowed: the Southern frontier of the West, a world in its infancy, incomplete anxious to become established, in a hurry and sometimes falling flat on its stomach. But the final aim of that obstacle race in which Latin America competes is very clear and nothing would help us so much to achieve that aims as that Western Europe would understand that our fate is linked with its own and that the desire of our people is to achieve prosperous and just societies within the system of liberty and mutual tolerance which is the West's greatest contribution to Humanity.

To the much that united us in the past we can add another common denominator that unites us Spaniards and Latin-Americans today: democratic systems, a political life marked by the principle of liberty. Never in the whole period of its independence has Latin America had so many democratically elected and representative governments as at this time. The dictatorships that survive are barely a handful and all them seem to be on their last gasp. It is true that our democracies are imperfect and precarious and that our countries have a long way to go to achieve acceptable standards of living. But the important thing is the path is being followed, as our people want - they let it be known ever more clearly every time they are consulted in legitimate elections - within the ambit of tolerance and freedom which Spain now enjoys.

For our countries what has happened in Spain in recent years, has been a stimulating example, a source of inspiration and admiration because Spain provides the best example for our countries that the democratic option can be possible and genuinely popular. Twenty eight years ago, when I arrived in Madrid as a student, there were those who smiled at talk of a possible democratic future for Spain with the same scepticism as they show now at talk of democracy for Bolivia or the Dominican Republic.

To many it seemed impossible that Spain could conquer a tradition of extreme intolerance, or revolts and armed coups. Nevertheless, all recognise that the country is an exemplary democracy in which, thanks to the very clear choice of the crown, political leadership and of the Spanish people, mutual democratic toleration and liberty seen to have taken root in an irreversible way.

The reality makes us Latin Americans proud and encourages us. But it doesn¡t surprise us; as it was possible here, it is possible over the sea in our land. Therefore to the many motives that present themselves to us we should definitely add this: the will to struggle, shoulder to shoulder, to preserve the freedom already attained, to help recover it for those from whom it has been snatched away and to defend it for those for whom it is threatened. What better way to commemorate the fifth centenary of our common adventure?

Until recently the word 'hispanidad' (spanishness) reeked of unfashionable neo-colonial nostalgia and authoritarian utopia. But remember every word has the content we want to give it. 'Hispanidad' rhymes with modernity, with civility and, especially with liberty. Everything will depend on us. Let us do the pirouettes that 'El Lunarejo' liked with those two words: 'Hispanidad' and 'Libertad': Let's united them, re-unite them, establish them, marry them and may they never again be divorced.

End of main content