Main content

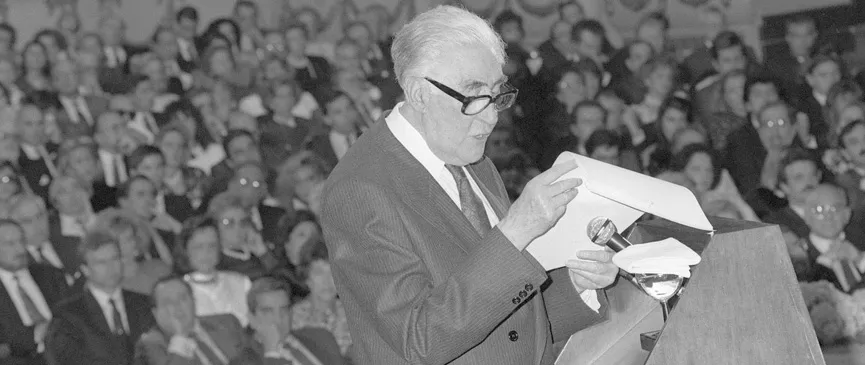

Ricardo Gullón Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 1989

I have received from the Foundation Prince of Asturias the charge of addressing you on behalf of this year’s Laureates and of expressing our gratitude for the conferral of these Awards. I am more than pleased to fulfil this commission which, furthermore, places me in a position to share with you a number of reflections and ideas that are deeply-rooted in the consciousness of the person addressing you.

I shall start by stating what –in my opinion– the Prince of Asturias Foundation stands for and what it has achieved through its activities: to place Asturias and Spain in highly visible position on Europe’s cultural map. By including in its lists of laureates prestigious figures from literature, the arts, music, science, politics, et cetera, it has shown intelligence in including the vast plurality of a world in permanent mutation and choosing competent, neutral juries for these Awards, the members of which are considered the foremost in their fields.

The valuing of effort, of the will to serve mankind within the respective scope of action of each laureate outweighed any difference in ideology, religion or nationality. Reading the list of the laureates in the nine years the Prince of Asturias Foundation has now existed, the richness and significance of a group in which personalities of the most diverse pedigree coincide is a matter for surprise.

The idea was conceived in Asturias and the Foundation assumed the undertaking of making it a reality. Asturias, a land where myth and history merge, a land of legends, a land of dreamers and practical men, of simple songs and dances, characteristic of a people disinclined towards the empty puffing up of the solemn. The collective soul of this people is renewed as needs be without departing from its traditional substance.

If my words had any lyrical brilliance, I might perchance dare to sing this corner of our country where, for more than half a century, I have had the luck to experience its fortunes and misfortunes, its festivities and its sorrows. Linked to Asturians by inheritance, marriage and residence, I admire –as did my father, nostalgic of the years he spent in Oviedo right until the end– the firm step with which Asturian approach the future, their energy to face up to problems without ceasing to be faithful to ways of life handed down to them from their elders. On the outskirts of the industrialized city persist the woods where the water nymphs –known as xanas here– live in their leafy nooks and crannies, still as seductive as two centuries ago.

I notice in this region’s sharpest thinkers a highly justified concern for environmental pollution. Could such beauty be corrupted and disappear under the rule of industrialization? I do not wish to believe so: its valleys and mountains still enjoy the clean, transparent air that Armando Palacio Valdés, Leopoldo Alas and Ramón Pérez de Ayala enjoyed and praised.

Three names of writers who loved villages and the countryside, light veiled by mist and air rinsed by the rain. They reinvented their beauty with words, as did Evaristo Valle with colours and lines. They –and not only they– preserved and transmitted images, emblems and symbols of a dreamed of country which vibrates in both the dream and the dreamer. These men created an Asturias of the mind whose kinship with everyday Asturias is perceivable, even if invention transports us to another plane of understanding. Stories and pictures allow us to better visualize the substance of the “patria querida” or beloved motherland evoked in the song.

And said word, the word “song”, the whispers of the breeze, the murmurs of the beech grove, the echoes of the rural pilgrimage and feast manifest in the form of melodies in which vigour and melancholy alternate. Songs of the past that the old hear with nostalgia and the young renew in fiestas propitious for love making. Life’s voices renewed in the corridors of time, today like yesterday and never identical in the “always” of continuity.

Asturias. Those of us who we have experienced its tenderness for so many years carry it in our blood and we are grateful –as I am grateful– for everything we owe to its spirit.

Now, you will allow me to present to you certain concerns about subjects related to the changes experienced by contemporary society in the sphere of Culture. The impetus given to scientific research over the last hundred and fifty years has produced results of extraordinary value. There is no better justification for such research than the progress achieved in all –I say, in all– sectors of science, from biochemistry to electronics and including the splitting of the atom.

The consequences are obvious and can be seen by everyone –if they wish to do so– for what they are, in terms of their variety and even more so in terms of their contradictions. Not everyone manages to distinguish between fortunes and misfortunes, dazzled by the advances that have radically changed the ways of life of “Western society” (by the term “Western”, I mean the prosperous countries, whether they are located in the West or not).

Wise observers of this society have noted that the progress achieved in science and technology has not been accompanied by parallel moral progress. The imbalance, I believe, is increasing day by day, and it is mandatory to ask whether a type of education devoid of the necessary ethical mainstays does not contribute to this increase. Einstein and Oppenheimer displayed their misgivings regarding the mortal use of the discoveries of the physics, and analogous reservations will have to be maintained in other sectors: such as genetics, for instance.

If the expression “art for art’s sake” has been declared defunct, it is vital to do the same with its parallel expression: “science for science’s sake”. No: science –and art– for humanity’s sake. The warnings can be heard to echo out before the signs and signals of dehumanization. The role played by ecologist groups, when not tainted by politics, is one of postponing –postponing, at least– the punishment inflicted on the planet by least scrupulous stratums of society.

The protection that states provide the sciences capable of improving the quality of life and of contributing to the levelling out of social inequalities is warranted. What is unwarrantable is the unbelievable discrimination of those who strive to uphold human values in our society. This discrimination occurs, as it presently does, when Science Faculties reject –and rightly so–insufficiently prepared students, who will, however, be able to enrol in the Faculties of Arts and Law. What a pernicious allocation for those who are to study something they are not interested in and how offensive for those attracted by the Humanities, so unjustly placed in the lower echelons of the university hierarchy.

The Humanities are the soul of the University, their ideal centre, their conscience. If the soul is relegated to an ancillary role, the “soulless” or –at the very least– bleak University will lose its guiding role in intellectual life and in the country as a whole, which, lacking a compass, will randomly drift in the murky waters of particularism.

Reflected and safeguarded in the Humanities, Spanish Humanism is concerned with “flesh and blood man”, present in the meditations of Unamuno, the everyday preacher of complete humanization. Ortega took a stand against dehumanized art, while Eugenio d’Ors developed his Science of Culture around man who works and plays. From these and other teachers, we learned to live in the tangible and earthly, without forgetting that it is possible to fly: roots and wings, as Juan Ramón Jiménez put it.

As a lecturer and literary critic, I am disturbed to behold the spectacle of the disintegration of the University in which I was educated and in which I lived for years. I ignore the diversity of factors involved in this collapse and am especially alarmed at the lack of interest in reading shown by most young people. When their grandparents and their parents attended university, they knew that they were joining a community of readers; emulating them was necessary to put themselves on equal terms, assimilating in the lecture halls and in books the knowledge that they transmitted to them.

Years of learning and education which are nowadays rejected by a considerable number of young people with hardly any passion for reading.

The university of this city used to be called the Literary University and responded fittingly to the adjective. Until the end of the last century, the centrality of the Humanities was undisputed; subsequently, the chronicle of the university describes their gradual relegation to areas of lesser importance.

Interest in literature declined and continues to decline: the competition with audio-visual media and sports that are seen more than practiced, except by professionals, is tough. Some are put off by mental apathy, others by laziness, these others by lack of preparation... A few persist: they constitute Ortega’s “select minority”, Jiménez’s “immense minority” and are usually reviled rather than praised: aristocracies, even those of the intellect, are not fashionable. What a shame! If those belonging to this group are characterized by their willingness to serve, why regard them with suspicion?

I do not know whether the lack of interest in Literature is due to ignorance of the effects that its works can produce in the reader. The inventions of human talent lead to knowledge and recognition: to in-depth knowledge of the mechanisms of behaviour and the causes of feelings. In Francesca and Beatriz, we discover the substance of the eternal female, while with Iago, Don Juan and Sigismund we became aware of ever valid male archetypes.

Novels, plays and poetry ease the weariness of the tired, distract the sad from their sorrows, delight the imaginative and edify us all. It is not necessary for the writer to set out to edify the reader; by the single act of writing a novel, a play or a poem the writer instructs and enriches the reader. In fact, we live in waiting –in ignorance– for the enlightening word. Whoever deciphers a literary text demonstrates their ability to learn and to breathe life into the word, discovering the patent lesson in writing and silences.

Text and reader sometimes fit together seamlessly: both participate in the invention. I have seen how students are surprised by their dazzle: they feel the page throbbing and dare to think that this palpitation is to some extent their own work. Ana Karenina and Ana Ozores, Mr Pickwick and Julien Sorel live and inhabit the reader’s mind with such vigour that he or she refuses to reduce them to verbal constructions, to functions in the structure. The most arduous task for a lecturer of literature possibly consists in leading students to a second-degree perception of actors and incidents. The reality of the text resists being diluted by the rigours of theory: love and death continue provoking feelings in readers and spectators, especially in the young, which cannot be called literary, although they stem from Literature.

The teacher is not mistaken if he or she respects the code of sensitivity when orienting pupils towards the depersonalized horizons of textual analysis. Falling in love at the right time with the heroine, provided that they reflect in the second movement on how and by what means words managed to achieve that effect. To induce them to reflect, that is to turn their gaze on their emotions, is already in itself to accustom them to the intellectually beneficial exercise of opening up their minds.

Time and again, we lecturers of literature encounter the distension produced in students by the reading of provocative imaginative works and it is in this respect that we can speak of didacticism. Instruction can exist alongside entertainment and stimulus: from Don Quixote, they learn about the misfortune of someone determined to reinstate the heroism of yesteryear in a world that no longer needs it, and, by analogy, the risks of spiritual anachronism and of differences in perspective.

The discreet teacher facilitates the understanding of the text by means of associations that reveal its meaning. The task of the teacher is to train students in the perception of forms, the understanding of situations, the visualization of structures and the like, a task that is so much more useful when the initiative is left to the students themselves. When they approach the text without feeling forced to do so, with the freedom to choose and even err –rectification shall eventually impose itself–.

The contributions of theorists to the analysis of forms with a preference for content has been beneficial for the study of literary works; even more so was the fact of understanding the former and the latter in such a way that it is possible to affirm the truth of something like: form is content; form –let us recall– obliquely includes time and space, matter transfigured into substance, peculiarities of diction, the voice giving shape to form, and enunciation –and within it, the enunciated–, in short, all that creation constitutes.

Creation, creator, maker, inventor... So many suggestive names for the primordial deed! From nothing and by means of the differential instrument of man, the word, something new emerges, something both valuable in itself and for its recipients and beneficiaries. This begs the –undoubtedly rhetorical– questions: Will it be necessary to stop the flow of creation? Could obstacles be placed before it in the name of disputable priorities? My categorical answer is no! On a page of science fiction, harassed men become books which give life to them. I am sure that literary invention and the fervour for the Humanities will never vanish.

They might become a thing of the past, be scorned, declared incapable of serving present-day man, negativism may relegate them to the suburbs of the consumer society, but there will never be a lack of voices that defend Humanism and institutions like this Prince of Asturias Foundation that recognize their meaning and their value.

Let us convince the sceptics of the need to maintain and even exalt Humanistic studies, around which –as until now– Culture should revolve. Culture and culture alone constitutes the secure bastion against the barbarian invasions which have so often threatened to destroy it before finally being converted by it. As opposed to utilitarian currents, Culture, the honour and glory of Man, will keep its flags flying on high. That is what I hope and that is what I proclaim at this solemn moment of contemporaneity.

End of main content