Main content

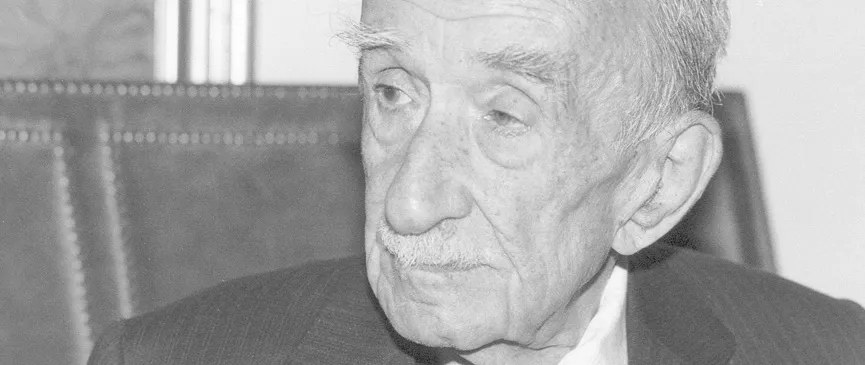

Emilio García Gómez Prince of Asturias Award for Communication and Humanities 1992

Your Serene Highness,

Being voted by so many highly-qualified jury members for an award bearing Your Highness' glorious title from one of our country's most distinguished Foundations, and being handed the award by your very person - Spain's hope for the future - in the presence of Her Majesty the Queen, are nigh on unsurpassable honours that not only inspire a frisson of joy but also impose a gladly-accepted debt of gratitude that the award winner will never be able to repay to your Highness, the Jury Members and the Foundation.

The onus of responsibility weights even more heavily on my person, for it is both my pleasure and my obligation to speak on behalf of the other Spanish award winners, any one of whom would have spoken with greater aplomb and authority. I hope at least to be a true spokesperson for the sentiments of this year's laureates, whose merits have already been heralded, and who yearly swell the legions called to rank before your Majesty to vindicate Spanish culture and render public homage to this marvellous Principality.

My responsibility also encompasses brevity, and as time does not allow consideration of any of the major issues, I shall confine myself to making a number of observations on lexicography. After all, I am primarily a linguist.

I think that it is very fitting that 'Concord' rather than 'Peace' - as it is called elsewhere - figures amongst the Awards. In the Lexicon Stock Market - as Mr Juan Velarde is only too well aware - the noble term 'Peace' is part of a present-day bear market. Peace is all too often the counterpoise of war (Tolstoy's 'War and Peace'). A 'cold war' will give way to a 'frosty peace'; even 'hotly-contested wars' - which mankind in his innate evil, in his 'original sin', has proved unable to eradicate - often fizzle out into 'frosty peaces'. 'Peace' is gradually coming to mean merely 'a lull in activities' or 'a calm', even though there was far greater scope to its original meaning, particularly as applied in the term 'God's Peace', which some natives of far-flung corners of our world still use as a term of welcome. In contrast 'concord' is more loosely tied to 'discord', and so does not suffer so frequently from alternation. Moreover, the heart - the seat of love and the noblest of human organs - beats within the syllables of 'concord' In the preface before the consecration we are invited to lift up our hearts: 'sursum corda'. The heart represents ebullient life and ardent fire, and becomes a worthless appendage when not warmed by the blood. 'Concord' is a beautiful word.

The juxtaposition of 'Communication' and 'Humanities', which graces the name of my award, is harder to fathom out. Nowadays, different meanings are given to the word, as each sees fit. It is most frequently used in the sense of 'the media for communication, i.e. the mass media'; however, if that were the meaning, I would hardly deserve the award, for although I have indeed turned my hand many a time to journalism in the course of my long life, I cannot claim the honour of being called a 'journalist'. I would prefer to apply the more ingenuous meaning of 'communication' of one culture with others, which is nearer in meaning to 'Humanities'.

However, there also turns out to be more to the term 'Humanities' than meets the eye. When I was still in my youth, 'Humanities' referred almost exclusively to the world of the classics. A 'humanist' was somebody who knew Greek and Latin and was imbued with the Greek and Latin spirit. The word has expanded its meaning in our times to include what we rather ambiguously call the 'Human Sciences', perhaps as used by Terence with the sense of 'that which relates to the human'.

Whatever the case may be, Oriental Studies (save for Hebrew) could not be assigned to the Humanities when I studied them. 'What a fine figurehead scholars of the Classics have lost!' they used to say about my teacher Asín, just as I was seen as a 'deserter' in much smaller circles when I shelved Latin in favour of Arabic. I once wrote, I do not recall where, that we were confined as Arabists to the ghetto of the extravagant and to the outskirts of the Humanities. How times have changed! Modern times have witnessed a spectacular volte-face. Intricate ornamentation, the poetry of algebra, Mozarabic trigonometry, the whole gamut of Arabic knowledge and know-how dovetail far better nowadays into advanced science and precious abstract art, represented in this year's awards list by Federico García Moliner and Robero Matta. Exquisite Islamic refinement goes well with the subtle cosmopolitan elegance of my colleague Francisco Nieva. A simple Arabist like myself may have been given the award for having used Arabic to open up channels of communication with them (which is where the concept of 'communication' comes in). As if you warn me not to overstep the mark, I have been summoned to this ancient land of Asturias, the heroic birthplace of the Reconquest, though I have always maintained my faith in my roots.

Your serene Highness,

Although not with the same power and rhythm as our dear Miguel Induraín, I have been racing against the clock in a time trial, and I have reached the finishing post with just enough time to pledge our heartfelt, respectful loyalty to you and to vouch our profound gratitude to you all.

End of main content