Main content

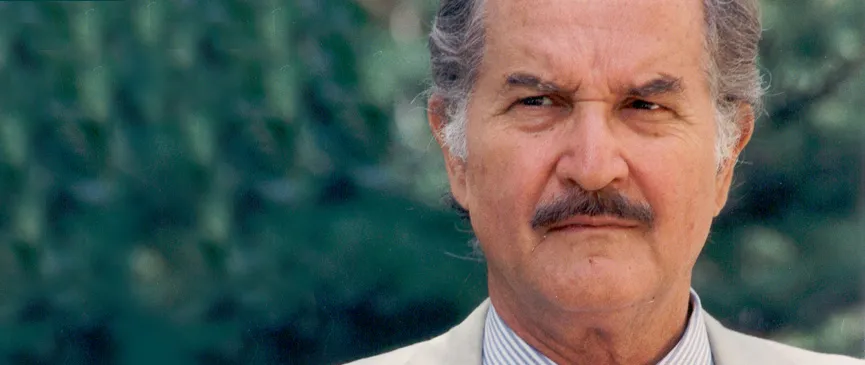

Carlos Fuentes Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 1994

Your Majesty,

Your Highness,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

It is with great honor that I thank you, Your Highness, on behalf of all the recipients of the 1994 awards, and applaud you for the generous acknowledgement that you annually bestow on the different men, women and groups who work in the fields of Communication and Humanities, the Arts and Sciences, Investigation, Sports, International Cooperation and Concord which, as Shakespeare once said, is humanity's interior music.

It is also the essence of peace, which a great kind and poet Solomon, carried in his song. Peace to all, to those near and far, to those seen and unseen, to the forgotten and to the marginal. That is why, the Prince of Asturias Award for Concord is dedicated this year to the needed childhood, a childhood that is threatened today in too many of the streets of this planet.

Being spokesperson for such a rich, diverse and, need I say, talented group is as great an honor as it is a difficult task.

We differ in profession, nationality, age, sex, however, since antiquity, it has been our tradition to join diverse merits and occupations in a common hymn: and what makes us different is as important as what makes us one.

Pindar, the great Greek poet of the Sixth Century b.C., left us with a choral song in which distinguished Olympic athletes, musicians, poets and statesmen were jointly praised.

However, his poetry belongs to a world of Homeric feats. Such a world was aware that the triumphs of peace walked hand in hand with the horrors of war and that both were contenders for glory, but that, once it lost its mask, the glory of war revealed its true face: death.

Let us remember the terrible words that Achilles uttered to his postrated victim:

"Come now, my friend, you too have to die.

Patroclus war far greater than you, and, yet, he's dead".

Simone Weil, the great Judeo-Christian philosopher, uses this example to remind us of what Homer already knew: the empire of violence is infinite. It can be as big as nature. Imagine, if you will, this horror, a violence so big that if becomes synonymous to nature!

Such a violence can only be dispelled by three words of advice: don't admire power, don't detest the enemy and don't scorn those who suffer.

This is the other side of Pindar's Olympic song.

Our age has been deprived of a tragic culture, and, as a result, it has not known how to respect these words of advice.

The Twentieth Century has worshipped power, has destroyed the enemy with premeditated and quasi-scientific malice and has piled sorrow upon sorrow onto the shoulders of suffering beings.

Today, as we approach the end of the Century and the Millenium, we make the most of an exalting ceremony such as this to reflect on the need to create a common civilization, one that is both diversified and shared, and we do so in order to be deserving of our awards and the glory that is bestowed on us by the homeland of Jovellanos and Clarín, two men who, through their deeds, showed us how far the human spirit can go when it is driven by the desire to add beauty and truth to the earth.

Allow me, Your Highness, to seek protection for my words of tonight under the aegis of two illustrious Asturians: Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, the greatest thinker and statesman to ever lead us down the road of reason and good guidance, and Leopoldo Alas "Clarín", the greatest novelist to ever take us down the path of imagination and sensuality. By presenting reason and sensuality together, without sacrificing intelligence or human pleasure, these Asturian thinkers have given our plural, though shared civilization a great lesson in beauty and humanity.

Tonight, we gather in Asturias, the home of the rebel patriot, Pelayo, and from its mountains heights, we can clearly distinguish what brings us together: a common civilization.

It is the Mediterranean that makes us one, our Mediterranean, its culture and the sea that embraces us from Israel, Palestine and the Levant through Greece and Italy to Iberia and beyond. The waves of the European Mediterranean reach as far as the American Mediterranean -the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico-, and there they fertilize a land rich in language: Castilian, English, Dutch, French and all the verbal crossbreeding that was born on the plantation and the slave ship.

The Mediterranean influence reaches down to southern shores, the Maghreb and Egypt, up to northern limits, which are also the tributaries of the Atlantic and the Baltic, of Greek philosophy, Roman law, Arabic science and Judaism.

As I speak, I stand on Spanish soil, where all these values converge, making this ceremony a commemoration and a regathering of these cultures.

It was not in vain that Christians, Jews and Muslims coexisted here during five centuries.

It was not in vain that Saint Ferdinand, King of Spain, saw himself as a descendent of three cultures: the Hebraic, the Islamic and the Christian and indebted to these three Mediterranean pillars; he had his tomb inscribed in Seville, on all four sides, in the four languages of a diverse but shared culture: Latin, Spanish, Arabic and Hebrew.

It was not in vain that Alfonso X of Castile, the scholar, brought Arab and Jewish intellectuals to his court to translate the Bible, the Koran, the Cabal and the Talmud into Spanish.

The prose of Spain -a prose that brings together the 400 million men and women in Spain and Latin America, not to mention the thirty million Spanish-speaking people in the United States- originates in Alfonso's court and is essentially the language of three cultures.

What a great example for the years of intolerance, persecution and exile that followed!

What a great warning so that we never again degrade our humanity through the barbarity of racism and xenophobia!

But will we know how to address a common goal for humanity, without sacrificing the unique contributions of each of its peoples?

It is our job to find out. The peoples of both Mediterraneans -those here and those there, those of Beirut, Tel Aviv and Jericho, and those of Veracruz, Cartagena de Indias and New Orleans, those of Alexandría, Tunisia and Algiers and those of Puerto Rico, Nicaragua and Panama, those of Palermo, Barcelona and Venice and those of Puerto Cabello, Santo Domingo and Santiago de Cuba- should aim to address a common goal, just as we who are being awarded here today should know what makes us different and be able to express what makes us one.

It was this shared language and culture that crossed the Atlantic to embrace the American coasts and continue an active and defiant civilization that went beyond the crimes of the conquest and the abuses of colonization, and gave to a counter-conquest and a decolonization led by Creoles, Indians, Mestizos, blacks and mulatos, who incorporated their own language to that of Spain and, through doing so, discovered that a good third of our vocabulary comes from the Arabic -words such as "acequia", "almohada", "alberca", "aljibe", "alcázar", "alcachofa", "limón", "naranja" and "olé"- and that half of our religion - from the Genesis to the Book of Daniel - is Jewish and that in our Spanish and Latin-American thought we cannot separate the Christian San Isidoro from the Jew Maimonides and the Arab Averroes.

There would be no Libro del buen amor by arciprest Juan Ruiz without The Collar of the Pigeon by Ibn' Hazam of Cordoba, and, without both, the converse Jew Fernando de Rojas would not have written the aurorean work of the renaissance city, La Celestina.

Gabriel García Márquez told me that one day, upon arriving at the Teheran airport, he was bombarded by reporters who wanted to know what influence Persian literature had had on his work.

As though illuminated by the Holy Spirit, the author of One Hundred Years of Solitude replied: The Arabian Nights.

Isn't every narrator a son of Scheherazade -that is, of the woman who told a new story every night so as to see a new day and postpone death?

Similarly, we cannot separate the work of Jorge Luis Borges from the great moral and ideal constructions of Judaism: the Cabal that governs the interwoven destinies of Tlon, Uqbar and Orbis Tertius and the Talmud that guides us in our delectable wanderings through the garden of forked paths.

Since the Sixteenth Century, America has been sending verbal caravels back to Spain to ply a new Mare Nostrum. The Spanish chronicles of Bernal Díaz, for example. The indigenous chronicles of Guamán Poma de Ayala. The mestizo chronicles of the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, who, from his Peru of the Viceroys, gives us this advice: "There is only one world".

Gutierre de Cetina and Mateo Alemán came to Mexico from Spain, Juan Luis de Alarcón went from Mexico to Spain and since them, the Mediterranean flow has not ceased: Spain owes as much to Nicaragua's Rubén Dario as America does to Granada's Federico García Lorca, and as Spain does to Chile's Pablo Neruda, and as America does to the exiled Spanish poets, Alberti, Cernuda, Prados and Altolaguirre.

All we need is the memory of this to understand that our culture is two things: migratory and Mestizo.

It is a melting pot of many races and cultures, and this is the reason for its continuity and strength.

But it is also the fruit of many exiles, migrations, moves; it is the impetus of its pain, its courage and its virtue.

We have a culture that is Mestizo, migratory. Today both these qualities are in danger, and this happens at a time when, after fifty years of sterile cold war, exclusive ideologies are making room for the inclusive cultures that have been put aside for a long time, because they did not fit in the bipolar refrigerator of the East-West conflict.

Cultures as the protagonists of History. We are not used to his challenge, especially now, when the vehicles of culture are not only writers and artists, businessman and statesmen, but also the emigrant workers and labourers who are forced to obey the demand of the market in order to break the curse of poverty.

Our pilgrim cultures have become universal. They move in vast currents from South to North and from East to West, carrying with them workers and their families, and their prayers, their kitchens, their memories, their greetings and songs and laughter and dreams and a desire to defy prejudices, to reclaim equity alongside identity, to keep their own cultural profile in an unfixed world that is determined by immediate communication, a growing technology and the flux of both the capital and labor markets. These pilgrims are trying to enrichen the national identities of those countries into which they are integrating.

Can we deny these secular legacies their right to exist? In a universe of such rapid change, they can turn into essential, if not lifesaving, contributions to a future that is as complex as it is unpredictable.

The French romantic poet Alfred de Musset wrote the following words at the end of the Napoleonic era: we live with one foot on ashes and the other on seeds. The same can be said for us today. We don't know how to separate the past from the future, nor should we have to, for they both accompany us in the present.

Our Century has been a brief one, full of contradictions. It began in Sarajevo in 1914 and ended in Sarajevo in 1994. It has been a Century of unmatched progress and incomparable inequality:

The biggest scientific step forward and the greatest political step backward.

The voyage to the Moon and the voyage to Siberia.

The glory of Einstein and the horror of Auschwitz.

The relentless persecution of entire races, wars not directed against armies but against civilians, six million Jews murdered by Nazism, two million deaths in colonial wars and forty million children that die unnecessary deaths every day in the Third World.

Self-determination for some peoples, but not for others, be the latter sometimes neighbours of the former. This is an irony worthy of Orwell: all nations are sovereign, bus some are more sovereign than others.

We are in need of renewed international organizations that reflect a new world composition. In 1994, there are 200 independent states; in 1945, the year that the UNO was founded, there were 44. Today's world is one of battles over transnational, national, regional and tribal jurisdictions, one of opposition between the global and local villages, between the technological village of Ted Turner and the memory village of Emiliano Zapata, between the happy robot that lives in the pent-house and the tribal idols that survive in the basement. At present, we are undergoing a painful passage from a volume economy to a value economy to a value economy, with the consequent sacrifice of millions of workers. And these workers are the victims of the following paradox: bigger productivity is coupled with bigger unemployment. We are influenced by a worldwide info-net, but we are informed of very little, because we have lost the organic relationship between experience, information and knowledge.

This is an age of information explosion and significance implosion.

However, all these conflicts can be considered opportunities; after all, they have the possibility to bring about contact, interchange, dialogue and the concord. Imagination and humanity needed to create that one world which the Inca Garcilaso foresaw and which forces us today to acknowledge ourselves in a common problem:

There are beggars in Birmingham, Bogota and Boston.

There are homeless in London, Lima and Los Angeles.

There is a Third World within the First World, but the problems of women and the elderly, education, crime, violence, drugs and aids make no distinction between a First, Second, Third or Fourth World.

Just as there are children who are being murdered by vigilantes on the streets of Rio de Janeiro, there are children who are being murdered by other children in the ghettos of Chicago, and children who are caught in random gunfire in New York.

Yes, there is only one world: this is what we're are told by all the hopeful artists, statesmen, athletes and scientists who are being awarded here today, and, especially, Your Highness, by the three recipients of the Awards for Concord: Spain's "The Messengers of Peace", the Brazilian Movement of the "Meninos da Rua" and the British organization "Save the Children".

Political willpower has shown us that it is possible to reduce the empire of violence and put into practice the Homeric desire to respect the old enemy and to love those who suffer history.

The South Africa and the Middle East of today -and, with any luck, the Ireland and the Caribbean of tomorrow- are examples of how diplomacy and negotiation are once again plausible means to avoid violence and establish fraternity.

Tonight we toast to us, the men and women of the future, for men and women of the future are what Shimon Peres has asked each and every one of us to be.

Tonight Yasir Arafat and Yitzak Rabin honor our diverse but shared humanity, they stretch the Mediterranean even farther and give us the tranquillity that Moses found when he arrived in his homeland and stopped being "a stranger in a strange land", a tranquillity which the Palestinian poet Mahmud Darvish brilliantly defines in his poem Reflections on exile: "Seal me with your eyes / Take me with you wherever you are / Take me with you as if I were a toy or a brick / So that our children do not forget to return".

Your Majesty, Your Highness, Ladies and Gentlemen:

I would like to end this address with a very brief personal account.

I interpret every award that is given to me as an award to my country, Mexico, and the culture of my country, a culture that is fluid, alert, non-ideological and an inseparable part of the dramatic process of democratic transition and social affirmation that we, 90 million Mexicans, face today with divided hope.

I hereby deem my country and its values this award, the Prince of Asturias award of Letters.

However, I -through Mexico and Mexican civilization- join all of you, together with the Asturian civilization of Jovellanos and Clarín, those great men who are Asturian because they did not fear the risk involved in political, artistic, economical and moral creation.

And, through Asturias and Mexico, I join all of you in the celebration of a culture for the new Century: a culture of intrusions, never of exclusions, a culture that will reduce the empire of violence and increase that of peace and culture. For it is the empire of peace and culture that is, when all is said and done, at the service of something supreme: the continuity of life on this planet.

End of main content