Main content

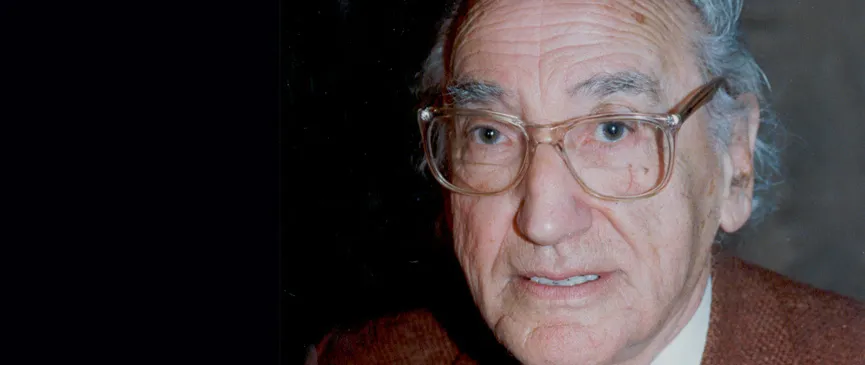

Carlos Bousoño Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 1995

Your Majesties,

Your Royal Highness,

Most Honourable Ministers,

Most Honourable President of the Regional Government of the Principality of Asturias,

Most Honourable President of the Prince of Asturias Foundation,

Most Honourable Sirs,

Ladies and Gentlemen,

First of all, on behalf of all of us who have been distinguished this year by the Prince of Asturias Foundation in its various branches, I must publicly express my thanks for the award that has been bestowed on us.

There is no need to state —as the fact is irrefutable— the high esteem that this award which bears your name, Your Royal Highness, enjoys today in Spain, but also (I stress this because I know it to be so) beyond our borders.

Among the many merits of the Foundation that has brought us together here today, I wish to highlight, as perhaps the most significant, the international character of its guiding principles, which each year brings together Spain’s literary and scientific names in this theatre, together with those others from America who speak and write in our own tongue; and even, from outside of these branches, those of public figures from all over the world. For example, there are several foreign laureates among us today, such as the Algerian athlete Hassiba Boulmerka, along with statesmen of the calibre of His Majesty King Hussein of Jordan and Mario Soares, President of the Republic of Portugal, all so worthy of the laurel crown they have achieved.

And the fact that this internationalism seems to me to be perhaps one of the supreme virtues of this Foundation is due to the evidence that the weakening of the boundaries between different countries is becoming the great work that has started to take shape in the world in recent years, and which will perhaps soon heighten and extend it integrating character, along with the other movement that seems to oppose it, but in fact does not, as it responds, I think, to the same essential momentum: that of also recognizing, even pampering, the differences in the various regions of which each nation, in turn, consists. On the one hand, let us say, there exists the idea in today’s world of a united Europe; on the other, the linguistic and ethnic autonomies in Spain, Italy, Germany, Belgium, etc. Both are necessary and complementary, as I believe I have said since 1958. Let me briefly explain the reasons which, in my opinion, operate in such an important issue. By referring, for now, only to the trend toward large units, which is increasingly becoming the case, it becomes more patent once we notice it (although this is not the cause of the phenomenon, but only its main stimulus) that today’s world is, in fact, already unified in its essential, economic, scientific and technical aspects and even in the fashions of dress, thought or feeling.

Instant communication contributes strongly to union: planes, telephones and telegraphs are already things of old; while television, the fax, computers, and many other devices are a recent cause for amazement. And let us ask ourselves: Is there not a real contradiction, condemned as such to its early demise, between this apparent substantive unity and the extreme forcefulness of inexorable, radically separative borders? And while what I shall say is not the real cause either of the opposing tendency to protect the discrepancies of the parties involved (Walloons and Flemish in Belgium; Galicians, Basques and Catalans in Spain; and so on), there is no doubt that an important stimulus (I repeat: stimulus and not cause) of the strange, apparent paradox has to be the instinct not to destroy the wealth of beneficial variations that excessive standardization may entail. So, what then will be the sole cause of the two opposing phenomena: union above: Europe, etc., and an apparent tearing apart below; that is, the power of the parts and decreasing power of the wholes. Or to put it yet another way: a decrease in the power of great nations and institutions, in favour of its increase in their respective subordinations: “shadow power”, “power of minorities”, “power of the regions”, power of women —“feminism”— power of the colonies —“decolonization”—, and so on. In short: decentralization versus the progressive political centralization that the actions of rulers have entailed, to an increasing extent, since Louis VI the Fat in France (early 12th century) up until just a few years ago?

To what is this dual phenomenon, which bewilders us by its paradoxism, actually due? Since I cannot answer this question to its full extent, I shall make a gross summary. The growth of physical-mathematical reason, especially in the late 17th century and throughout the 18th century, reason that is, of course, a generalizing reason without exceptions, finally brought with it the ideas of equality among men, the abolition of the privileges of the nobility, as well as civil rights and human rights, all enshrined in the French Revolution. With the coming of Romanticism, and with such high achievements already assumed, this kind of reason, which until then had only brought benefits, began to be viewed with suspicion, as, by generalizing, it overlooked precisely the individual (in a time when the individual already mattered a great deal), and therefore life, which is always truly individual. A different form of reason was then sought, one that was not anti-life. After the trials and errors of Romanticism and Symbolism, life-related Ortegan reason represented the triumph of this trend, because it was a generalizing reason (all reason necessarily has to be so), but one which took into account the exceptions, the discrepant peculiarities of groups and individuals. The upsurge of the protest and hence the crisis of physical-mathematical or instrumental generalizing reason without exception, I repeat (Unamuno, Bergson, Spengler; Weber; Class of 27; Ortega; the Frankfurt School; the student rebellion of ’68), resulted in the gradual replacement of this life-related reason, which, by generalizing, entails, like the other kind of repudiated reason, the formation of increasingly larger groups (from political groups, the idea of the European Union, for example, through to those which might seem more trivial: the sale of goods in large shopping centres, let’s say). However, by attending with equal force to the parties involved, this life-related reason also led to the decentralization of the old centres and countries (in Spain, the State of Autonomous Communities) and the emergence of the previously silenced minor or partial “powers” which I named only a moment ago.

So: there we have the reason for the joy that I feel for the fact that, in its annual distribution of honours, the Prince of Asturias Awards do not make distinctions between nations or, especially, between nations that speak the same language, as this internationalism supposes the appropriate adjustment to the times in which we live, the pursuit of which is always good and even obligatory. Today more than ever, we should feel proud to belong to the defenceless, glorious race we call “man”, while never overlooking our painstaking love of the Western World, of Europe, of Spain, of the Basque Country, of Catalonia, of Asturias, where I was born, and undoubtedly, for my part, of Oviedo, a city where I lived the first nineteen years of my existence. How many times did I pass by this Campoamor Theatre at the age of five, ten, fifteen, eighteen! In fact, I received my first aesthetic emotions (as virginal and intense then as now) in Oviedo.

Your Majesties, Your Highnesses, Most Honourable Sirs, Ladies and Gentlemen: May the spirit of world brotherhood and respect for the differences between regions, between different minorities and different races, sexes and consciences spreads around the planet! And may examples such as those that these generous awards represent, open to Spanish literature, not only to the literature of Spain, and also open in other directions of more international scope also thrive and serve to unite all the endearing mother lands, large and small, of which we all, each one of us, are loving representatives!

On behalf of the this year’s Laureates, I insist once more that we know very well that we are not the only ones who deserve this honour, as merit is much more widespread than its fortunate samples taken from an annual cross-section of the world’s cultural body. Thank you very much. And thank you also to Your Majesties, Your Highness, Most Honourable Sirs, Ladies and Gentlemen for listening to me.

End of main content