Main content

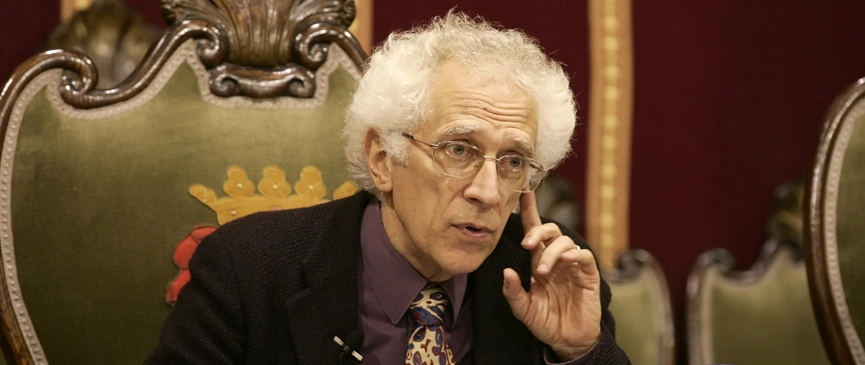

Tzvetan Todorov Prince of Asturias Award for Social Sciences 2008

Prior to the contemporary age, the world had never been stage to such intense circulation of the peoples who inhabit it, or of so many encounters between citizens of different countries. The reasons for this movement of peoples and individuals are many. The celerity of communications boosts the prestige of artists and of the learned, of sportsmen and women and of activists for peace and justice, placing them within the reach of men and women from all continents. The current speed and ease of travelling nowadays invites the inhabitants of the rich countries to practise mass tourism, while globalization of the economy obliges the elite to be present in every corner of the planet and workers to move wherever they can find work. The population of poor countries tries by whatever means possible to access what it considers the paradise of industrial countries, in search of decent living conditions. Others flee from the violence that ravages their countries: wars, dictatorships, persecution, terrorist acts... For a number of years now, to all these reasons which motivate the displacement of populations have been added the effects of global warming and the droughts and cyclones it entails. According to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees, a million people will be displaced in the world for each centimetre that the ocean rises. The 21st century presents itself as one in which numerous men and women shall have to abandon their country of origin and adopt -either permanently or provisionally- foreign status.

All countries establish differences between their citizens and those who are not: that is to say, foreigners. They do not enjoy the same rights, or have the same duties. Foreigners have the duty to subject themselves to the laws of the country in which they live, even though they do not participate in its management. Laws, however, do not tell the whole story: the framework they define includes thousands of daily acts and gestures that determine the flavour existence will have. The inhabitants of a country shall always treat those close to them with more attention and love than they do those whom they do not know. The latter, however, do not cease to be men and women like the rest. They are driven by the same ambitions and suffer the same needs; only that they are more prey to neglect than the former and plead for our help. This concerns us all, because the foreigner is not only the other; we were once the foreigner -or we will be-, running the odds of an uncertain fate: each one of us is a potential foreigner.

Our degree of barbarity or civilization can be measured by the way in which we perceive and welcome others, those who are different. Barbarians are those who consider that others, because they do not seem like them, belong to an inferior level of humanity and deserve to be treated with disdain or condescension. To be civilized does not mean having studied at university, or having read many books, or possessing great wisdom: we all know that certain individuals with these characteristics were capable of committing acts of absolutely perfect barbarity. To be civilized means to be capable of fully recognising the humanity of others, even though they have different faces and customs to ours; to know how to put oneself in their place and look at ourselves as if from outside. No one is definitively barbarian or civilized and each one of us is responsible for our actions. But we, who today receive this great honour, have the responsibility to take a step forward towards a little more civilization.

End of main content