Main content

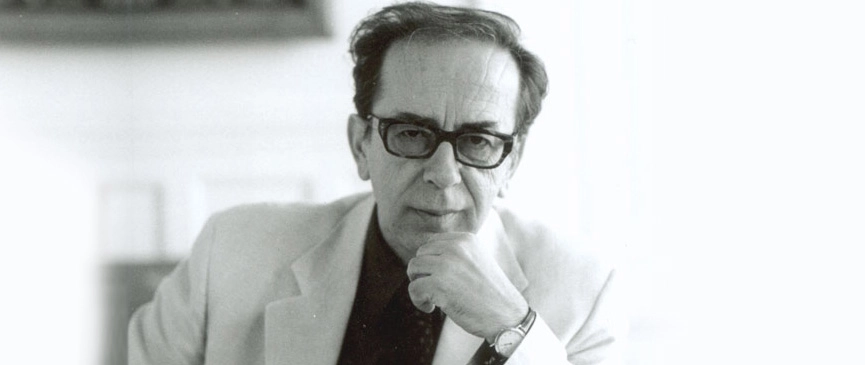

Ismaíl Kadaré Prince of Asturias Award for Literature 2009

It is especially satisfying for me to be present here today and to speak on this stage. This satisfaction is twofold, as it has all come about as the result of Literature, a universe to which I belong.

There have been and continue to be two radically opposing ideas regarding Literature: on the one hand, the ancient and somewhat naïve idea which believed that Literature, like the rest of the Arts, was capable of producing miracles for the world; and on the other, the modern and thus in no way naïve notion that Literature and the Arts are at the service of no-one but themselves.

Truth and non-truth are to be found intermingled in these two ideas. However, as I am a man of the Arts, I am inclined to believe in miracles.

A model exists for this paradigm: the myth of Orpheus. It has rightly been considered the most mysterious of humanity’s myths. Its essence is related to the authority of the Arts. Orpheus managed to achieve incredible feats and, although he did not manage to cross over the wall of death, he did approach the impossible more than anyone else.

I have mentioned this famous myth in order to get to another miracle that is much more trivial in appearance, though of the same nature. Twenty years ago, in my communist country, if anyone had suggested the possibility that an Albanian writer would one day receive an award in Spain, and moreover from the very hands of the heir to the throne, that person would have been immediately certified as mad, they would have put him in shackles and dragged him off to the lunatic asylum. And that would have been the lesser of two evils. According to a second version, that same person would have ended up in court and would have been tortured as a dangerous plotter.

Perhaps this scenario may seem somewhat overdramatic, but allow me to explain.

Apart from a brief period of friendship in the 15th century, my country, Albania, and yours, Spain, never maintained any sort of relations. Complete rupture, however, occurred in the last century when my communist country, famous for breaking relations –this was, one might say, its speciality–, cut off all links with Spain.

Nonetheless, as in all things in this world, the miracle of Literature also possesses a tradition. During the glacial age of which I just spoke, when no-one travelled between my country and Spain, a solitary gentleman crossed the impassable frontier as often as he wished, spurning the world’s laws. You will imagine who I am referring to: Don Quixote.

He was the only one who that communist regime did not manage to detain, which was precisely the easiest thing in the world for it to do –to detain, to ban. Don Quixote, whether as a book or as a living character, was as popular in Albania as if she had engendered him herself.

The following explanation might be found for this paradox: Don Quixote was deranged, and the Albanian State was no less mad; hence, it was logical for two crazy beings to understand one another. At the same time as I apologise for comparing the noble derangement of Don Quixote with the perverse insanity of my State, allow me to tell you that this was not so, and that the parallelism is related to another phenomenon.

I have made this long introduction so as to arrive at the main theme of my brief speech: the independence of Literature. Don Quixote crossed the Albanian border because, among other things, he was independent. When an Albanian writer, due to works written mainly in a communist territory and period, comes to receive an award from a Western kingdom, this occurs because Literature is –by reason of its own nature– independent.

The debate is a longstanding one. It has been and, perhaps, continues to be the main concern of this Art. As opposed to the independence of States, that of Literature is global. Hence its defence should also be… global.

This does not mean that it is any easier. Quite the contrary.

The independence of Literature and the Arts is an ongoing process. It is difficult for our mind to capture its true proportions. Accustomed as we are to independence mainly in reference to States, nations or even human individuals, we find it difficult to take it any further. To take it further means to understand that the non-dependence of the Arts is not a question of luxury, a desire to perfect the Arts themselves. It is an objective conditioning factor; that is to say, it is imperative. Otherwise, this parallel universe would not remain standing; it would have collapsed a long time ago.

The concept, as I said, is ancient. The expression “the Republic of Letters” is likewise ancient and well known. The tendency to see Literature as a spiritual world, of course, but at the same time with the material attributes of space, time and movement, is more than well known; however that does not suffice. We accept it as a parallel world of reference, but when the time comes to achieve a full vision of it, our narrow, conformist mind encounters problems in accepting this parallelism; hence its true independence. On saying independent, our old instinct immediately pushes us in the opposite direction.

We are unable to avoid the idea that the Arts, while they may not depend on States, doctrines, fashion, do depend, however, on something. We immediately think about our real world; in other words, about our own life. The idea that Lglobaliterature depends on life is now almost officially accepted at a planetary level.

I would pose a question that is heretical in itself: Is this true? The answer, for the time being, necessarily has to be twofold: the idea that the Arts maintain links with life, though only partially, cannot be ruled out.

Allow me, in the final part of my speech, to very briefly explain this semi-heresy.

Once we accept that the world of Literature and the Arts is a parallel world of reference, we have also already admitted that it is a rival world. And hence, given that rivalry normally leads to conflict –whether we wish it to or not– we shall have to admit that the two worlds of life and of the Arts will enter into conflict.

And conflict, there is. Sometimes declared, on occasion veiled. The real world possesses its own weapons against the Arts in this clash: censorship, doctrines, jails.

And the Arts also have means at their disposal, their fortresses, tools, in short, their weapons, the majority of which are secret.

The real world is sometimes implacable, ruthless.

A German Romantic poet imagined Dante Alighieri’s tercets sometimes as threatening pikes and at other times as instruments of torture for consciences tormented by crime.

But the struggle between the two worlds is more complicated than it seems.

The same German poet insisted that some have wearied the Arts with their enmity and others with their affection. Paradoxical though it may seem, there are many who justly harass them in the belief that they love them.

As you can see, the independence of Literature and the Arts becomes more and more difficult.

Nevertheless, we writers are convinced that the Arts will never raise the white flag of surrender.

Since I have mentioned this sad word, I believe that I must return once more to the vision of the two worlds confronting each other in anticipation of victory: the real world or that of the Arts.

Of course, there exist many differences between them, but there is one of colossal dimensions that stands out above all the rest. And it is the following. While the real world, in its conflict with the Arts, becomes so extremely furious as to rush forward to destroy them, in no case whatsoever, I repeat, in no case whatsoever, do Literature and the Arts ever attack the real world with the intention of harming it, but in fact fight to make it more beautiful, more habitable.

This is the absolute difference between the two. And in this case, this difference constitutes no other than the most sublime confirmation of the true independence of the Arts.

Thank you.

End of main content