Main content

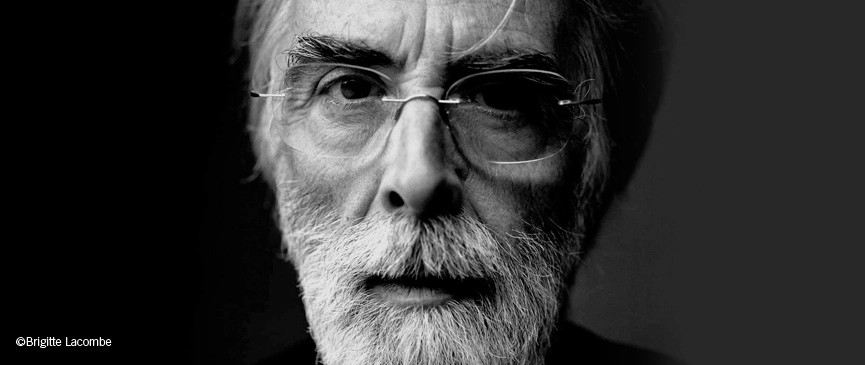

Michael Haneke Prince of Asturias Award for the Arts 2013

It is both a wonderful and yet difficult thing to be honoured. Why it is wonderful needs no explanation: we all love to be acknowledged. It is hard –and becomes harder with the weight of recognition– because the laureate wonders: why me and not one of the countless others who have accomplished the same or even more in my very same field? The search for the reason why is destined to fail, seeing as jury decisions and similar strokes of fortune or misfortune are of indecipherable origin.

If I am permitted to receive such a respected award, so charged with prestige in Spain, I wonder: what have you done Michael for Spain, or even Asturias, for them to be so kind to you?

Apart from being commissioned –thanks to Gerard Mortier’s invitation– to stage Mozart’s Così fan tutte at the Teatro Real in Madrid… nothing at all. I had never been here before, but rather had received gifts from this country from afar, via its literature, films, music and painters.

When –on the occasion of being in Madrid for the first time to stage the opera– I entered the room containing Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’ in the Prado Museum, I received a shock that I shall probably never forget. I actually started shaking and had difficulty remaining standing. I quickly left the room because I could not cope with it. But I had to go back. Whenever my obligations at the Teatro Real allowed me to do so, I would return to expose myself to the sensations that this work arouses in me.

I believe this experience with Art, which affected me with a vehemence almost unknown to me, can provide a delightful pretext to talk about the reason why I am here today as Laureate in the category of the Arts: the existent or non-existent possibilities of the influence of artistic creation or contemporary filmmaking.

Even though it is by no means certain that my own field of work, filmmaking, can even be considered Art. Since its invention at the beginning of the last century, the fairground nature of most cinematic production has done all it can to prevent it from being considered so.

Due to the particularity of being the most expensive of all artistic endeavours, while at the same time the one that is most ephemeral and dependent on the market, filmmaking finds itself in a particularly strained situation. The primary task of any film is to find as broad an audience as possible in order at least to cover its production costs and ensure the possibility of continuing to work with a certain degree of stability. As in other economic sectors, mistakes are not tolerated: those who repeatedly commit them are unlikely to have the opportunity to continue working. Added to this is the aggravating factor of competition from mass media, which, through their trivialization of aesthetic criteria and contents, necessitated by their dependency on ratings, do not precisely represent a sophisticated audiovisual school for the potential filmgoer.

In Europe, market dependence is only seemingly mitigated by subsidies. In effect, it is easier for filmmakers to make mistakes in our continent without this immediately implying a halt to future work. Compared to the open dictatorship of the US market, however, where the success of a film is measured solely in terms of cold, hard cash, the influence on filmmaking exerted by the television networks –which in Europe play a decisive role in funding– constitutes only an insignificantly lesser evil.

Film has a characteristic feature; it is much younger than all other art forms. So hopefully its best days are yet to come. Despite its youth, however, it has become guilt-ridden like almost no other form of artistic expression. Neither literature nor theatre has managed to stray so far from its particular vocation. At the very most, the visual arts have strayed as far as propaganda posters; and music, as far as military marches. Film, with its life-threatening efficiency when used as a tool for propaganda, has jeopardized the fate of thousands. It seems all too easy to deny the artistic nature of such films with no further ado, pointing them out as mere aberrations. However, there is no denying the high aesthetic competence of filmmakers like Riefenstahl and Eisenstein.

I spoke previously about my sensations when standing before Goya’s ‘Black Paintings’. Until then, I had never been confronted with such a directly physical effect from a painting and I think that most people also tend to assimilate Art in a more contemplative manner.

Film, however, is a means of subjugation. It has inherited the gimmicky strategies of all the art forms that existed before it and puts them to effective use. We all know how colours and larger-than-life paintings affect our heartbeat and overall wellbeing. Therein lies the power of film, and its danger. No other art form is as capable as film of so easily and so directly turning the recipient into a manipulated victim of its creator. This power demands responsibility. Who assumes this responsibility? Does the well-grounded suspicion of accepting film as an art form arise from this so often unembraced responsibility? Is manipulation not the opposite of communication? Is not communicability and respect in the presence of the ‘you’ of the recipient a basic condition in order to talk about Art in general?

Far be it from me to define the requirements for Art, nor do I even wish to limit its boundaries. I do, however, think that, in addition to the correspondence between content and form –essential for any form of art–, the capacity for dialogue is and must be an equally indispensable feature of artistic production; that is, respect for the autonomy of the other. Artists who do not take their partners –i.e. recipients– seriously, in the same way that they themselves wish to be taken, have no real interest in dialogue.

Film has all too often betrayed this basic interpersonal rule, which is also precisely a basic rule of artistic production. Manipulation serves many purposes, not just political ends. One can also get rich by stultifying people.

If, however, as in this case, the intention is to honour film in the category of the Arts through such a distinguished award as this and thus ennoble an art form, I believe it appropriate to call these conditions to mind.

I thank you wholeheartedly on my own behalf and also on behalf of my colleagues.

End of main content