Main content

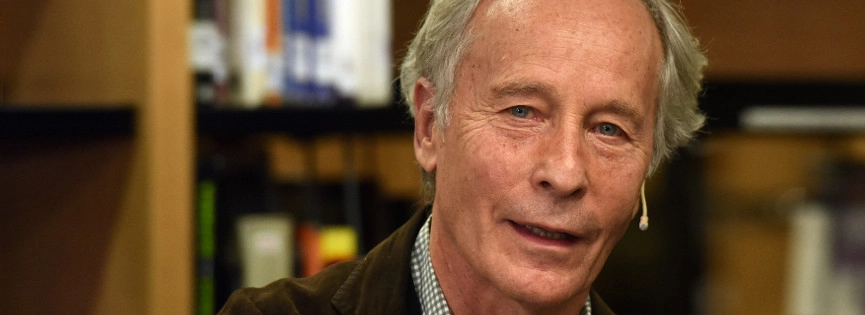

Richard Ford 2016 Princess of Asturias Award for Literature

Majesties,

distinguished laureates,

ladies and gentlemen:

You can imagine the great stir in my and Kristina’s house when we received an email from his Majesty one morning this summer, an email which revealed that I would unaccountably receive this splendid prize today. Being an American I have…well, let’s say I have ‘infrequent contact’ with….well…with any king. Much less a king and a queen as gracious as your Majesties. I’m sure I could get used to it. I’m a writer, I’m not that busy. I have time for such things. I hope his Majesty and I can keep in touch. I think writing to the king, and the king writing to a novelist (even without this prize) could possibly bring out a better side of both of us. Not that your Majesty’s best side isn’t always forward.

I suppose one might feel great humility standing here today, in this grand room, beside these remarkable people, and being here with you. I have a difficult time feeling humble, however, standing where Woody Allen has stood. I feel more a kind of joyous hilarity – just at the wondrousness of life – at what can happen in life. I’m sure all of us up here today feel this way. Though, we who’re writers, always experience the extraordinary-ness of what can happen. We know it, because we face it on the page every day. Ortega y Gasset wrote – and it’s an iconic observation for many here – Ortega wrote that ‘…Life is given to us empty. [Simply] existing becomes a poetical task.’ Receiving life ‘empty’ is just another way of saying that anything can happen. And writers’ poetical task is, with our imaginations, to make more happen, in order to increase the total of what can be thought about, and by doing that to enhance the richness and density of human possibility.

To me, this “poetical” task makes being a writer a joyous vocation, and an optimistic one – which a day such as today (if there could ever be other days such as today) almost perfectly embodies.

Writers are innately optimistic people – if not always innately joyous. After all, we don’t compete with each other – or we shouldn’t. When good comes to one of us, we all benefit by feeling encouraged that good can happen. A writer’s vocation also presumes that there will be a future where there will be readers for whom our books will be useful. It’s also the privilege of our vocation to make something be for others – something good – where before there nothing. My own failing as a writer – and it’s one that I’ve struggled with all my life, and maybe you’re the same – my failing is that despite being an optimist, I sometimes lose my touch for the joyous. Grave subjects make to me too grave. The world we see now, when we look around, is very grave, and doesn’t much encourage joy – as we Americans notice, when we think that Donald Trump could be our next President. Or as Spanish citizens notice when you consider income disparities and economic dismay. As French people notice, as Greek people do, or Eritreans fleeing Africa do. Joyous-ness seems to be fast-diminishing in the world. All the more need, I suppose, for acts of imagination to invent it for us.

The American novelist Henry James wrote once that there are there are no themes so human as the themes that reflect, out of the confusion of life, the relation between bliss and bale, the relation between things that help and things that hurt. What James meant was: that life is full of woe – as the Bible tells; but that woe can be joined to the blissful – even to the joyous – by acts of imagination. Like the joined faces on the mask of drama. I can’t generalize and say to you that great literature is always one way or always another way. But I can say that I would be a great writer – if I could be; and that my strategy for finding greatness is always, if I can, to write stories that connect the woeful with the joyful and in so doing to expand our awareness of human possibility, our awareness that anything can happen. This is another way of understanding Ortega and the poetics of existing. I mean, literature’s free, right? In a free society such as mine and as yours, no one tells us what to do. Nothing depends on the outcome of what we do unless what we write succeeds and is great. Why would we not try – as Cervantes tried –to imagine more, even though the reductive forces of convention tell us to imagine less?

When I look at television and read newspapers at home in the US, I see, all over the world, efforts by the intolerant among us to drive human beings violently away from one another. And yet for writers, our first source of consolation, and the embodiment of our optimism is each other. What gives me hope – and sometimes it’s the only thing that gives me hope – are acts that try to expand tolerance and acceptance and empathy for each other – beyond the conventional, the merely practical, and the mean. ‘Poetical’ acts, Ortega might say, which are also political acts.

I think of myself as a political novelist. Not because I write about politicians and elections and affairs of government and their consequences. I do that. But more because everything I’ve just said is what politics is. Politics determines the fate of humanity by expanding our ability to accept and find empathy and common cause with one another. If I could, I would rescue what we understand about politics and make the word useful again, make sure it suggests the necessity of imaginative response, to making something happen that replenishes our ability to live side by side – just as this can happen in literature – and have politics not be, as it’s become in the United States, a synonym for self-interest and cynicism and deception and absurdity. A synonym for woe.

A day such as today is a hopeful one. I know, I’ve received this precious Prize, so it may seem that I think everything’s looking better everywhere and that I have a special gift for the truth. I don’t. I’m just lucky today. Another day will come, and another writer will stand where I’m standing. I find that hopeful. But a truth that we can all see and recognize is that today represents a brief and encouraging, even a joyful, coalescence, a small and sweet version of the sort of coalescence the world literally aches and dies for, Something is being made to happen here. Literature from a ‘foreign’ language, about another culture, has been ingeniously translated; a brave and idealistic publisher has risked much to champion this writing and help it find its intended readers; librarians and booksellers have gathered; tv projects these proceedings all over the globe; their Majesties have given it their imprimatur; all of this certifying today not just as a literary event but also as a political event as well – both in the most basic and democratic sense of politics where free expression flourishes, and in the most emblematic and historical sense as well.

My presence here is just as a specimen, a surrogate for my colleagues all over the world who’re bravely making great things happen for the sake of tolerance and empathy and fate of us all, and often under circumstances so much more difficult than I’ve ever faced. I don’t go home to Syria. I don’t go home to Burma or South Sudan, where literature’s task of making something happen, of making an empty life poetical for the good of all, is often virtually impossible. And yet they do it. Possibly one of them will be here next year. My own personal undertaking, inspired by this Prize, is easy. It is simply to try not think of this wonderful gift as an award signifying that I’m at the end of my work, too old and over the hill; but to see it rather as a reason for encouragement, a strengthening of my resolve to make something happen that will be of use to the world. Possibly bring it joy. For this task, I promise you I will try my best.

End of main content