Main content

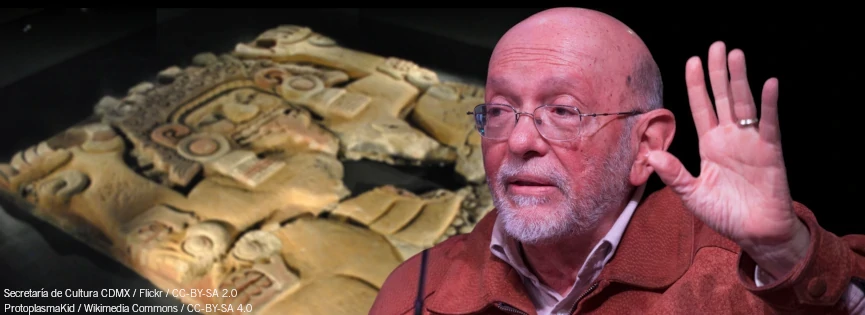

Eduardo Matos Moctezuma 2022 Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences

Awards exalt and prompt us to forge ahead. They establish a commitment between the recipient and his or her own conscience. Awards and recognitions are not only for the individuals or institutions on whom they are conferred; they are also for those teachers who instructed us, and for the institutions that provided us with support in the course of our academic careers and enabled us to develop our knowledge, both in terms of research and in the carrying out of our work.

I remember many of my teachers with special affection: the archaeologist Román Piña Chán, Johanna Faulhaber and the architect and archaeologist Miguel Messmacher. Also those who came to Mexico as a result of the Spanish Civil War and were a beacon of wisdom for me, namely José Luis Lorenzo, Juan Comas, Pedro Armillas and Pedro Bosch Gimpera, the last of whom was Rector of the University of Barcelona in those fateful days. I cannot fail to mention here those who, although they did not teach me in the classroom, were so via their works. I am referring to Manuel Gamio, for his comprehensive vision of anthropology; the archaeologist Gordon Childe, for his dialectical conception of historical processes; and the historians Miguel León Portilla and Alfredo López Austin, whom I have said form a duality that is expressed through the struggle of opposites and who are complementary opposites. Of the institutions, Mexico’s National School of Anthropology and History was my alma mater, in whose lecture halls I trained as an archaeologist. Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology is the institution to which I have belonged for more than six decades. I entered the institute as a student and today I am one of its emeritus researchers.

Digging into the past to bring it into the present has been the task that I have unceasingly carried out throughout my life. That modern time machine that is archaeology was the means to transpose time itself and reach out to the peoples who preceded us in history. Thus, history and archaeology situate us face to face with the societies of the past and show us that many of them were instigators of important advances and that, in time, powerful empires and rulers arose who, in their arrogance, believed that they would be eternal, but such was not the case. History is ruthless in its rulings. You cannot try to manipulate it or commit the mistake of misrepresenting it. Ignorance that often leads to lies is a bad counsellor. History is written by peoples. Peoples who shape better futures.

Mexico and Spain are linked by enduring ties. That is what I stated when I was informed of the decision of the Jury for the Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences. This is what I continue to assert on receiving this honourable award. What our two countries are today hailed from centuries ago, each swathed in its own respective history. The conjunction of the two occurred in the year 1521, which saw the meeting of two different ways of thinking, of societies that had their own vision of the universe. Alfonso Reyes, a universal man, has related that episode in his Visión de Anáhuac, when Hernán Cortés’ troops first saw the Mexica cities of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco in the middle of the lakes of central Mexico. His account of the event is the following:

“Later, the city had expanded into an empire, and the noise of a cyclopean civilization, like that of Babylon and Egypt, endured, though faltering, to the ill-omened days of Moctezuma, the Weak. And it was then, in an hour of amazement one might envy, that Cortés and his men (“dust, sweat, and iron”), having scaled the snow-crested volcanoes, appeared against the orb of resonance and glory –the sweeping cirque of mountains.

At their feet, in a crystal image, the picturesque city lay extended, the whole emanating from its center, the temple, so that its radiant streets were prolongations of the corners of the pyramid.” (Reyes, 1915)

In the first part of the conquest, the Mexicas or Aztecs were the enemy to be defeated by Hernán Cortés’ troops and thousands and thousands of indigenous allies, enemies of Tenochtitlan. Their military victory on 13th August 1521 was followed by the commencement of the second part: a spiritual conquest at the hands of the ideological apparatus represented by the Church, while the conquest of other regions continued to give shape to New Spain. Several centuries were to pass under the new peninsular order which entailed economic, political, social and religious changes. This state of affairs was interrupted when the insurgent forces were victorious and the new republic emerged in the year 1821. Independent Mexico began to follow a path of its own. A few years later, in 1836, our two countries signed the Treaty of Peace and Friendship and established diplomatic relations after long-drawn-out struggles. Mexico recognized Spain and Spain recognized Mexico as an independent nation; a good example for overcoming past grievances.

Throughout the centuries, history shows us that every war brings death, destruction, desolation, imposition, injustice and violence. Spain has experienced this first-hand; Mexico too. This is never forgotten, but neither can we anchor ourselves in the past and hold grudges, but rather we should look to the future. In this sense, Mexico and Spain must move towards a promising future.

All recognition entails honour, but also gratitude from those who receive it. The words of Miguel de Unamuno, Rector of the University of Salamanca, come to mind here, who, in October 1936, in that place of knowledge, uttered wise words that were soon silenced by intolerant voices that I would not wish to ever hear again on the face of the earth. These Awards that we receive today in this “home to the Muses” are an ode to intelligence. Universities and academies are the places where thought and reason are cultivated. The National Autonomous University of Mexico, with its prior history going back more than four centuries, has instructed thousands and thousands of men and women who, over time, have lent greatness to Mexico through science and the humanities. This is the institution that submitted my nomination for the Princess of Asturias Award. Its Rector, Dr Enrique Graue, has managed to steer the fate of our university with both dignity and prudence. The Mexican Academy of the Spanish Language, established in the 19th century, to which renowned specialists have belonged who bestow prestige on correct speech, is the other institution that endorsed my being considered for such a lofty distinction. My appreciation goes out to its director, Gonzalo Celorio, and to my fellow peers within it.

Today, in Oviedo, in the presence of Their Majesties The King and Queen of Spain, Her Royal Highness Princess Leonor de Borbón y Ortíz has presented me with the certificate that accredits me as the recipient of the Princess of Asturias Award for Social Sciences.

Thank you very much.

End of main content